Mr McIntyre, Raymond Francis

Date of birth

1879

Date of death

1933

Gender

Male

Place of birth

Place Of death

Biography

"Raymond Francis McIntyre 1879-1933 - M.N. DAY

Of the many New Zealand painters who left their native country to work overseas none has proved so elusive as Raymond McIntyre. The difficulties one experiences in coming to grips with the man and his work are due to the fact that he was a self-effacing and very private person, who took great pains to conceal his feelings from most of his family and friends. The resultant lack of knowledge has been frustrating, because the last few years have seen a growing interest in his work. Not only is the quality of his painting superb: more than that, it shows an acute awareness of contemporary trends in European art of the early twentieth century.

Born in Christchurch, McIntyre was one of seven children of George McIntyre, a one-time mayor of New Brighton. His formal education finished when he was fifteen years of age, and he began art studies at the Canterbury School of Art, where he was taught by Herdman Smith and Alfred Walsh.1 A break in his training occurred between 1901 and 1906, during which time he shared a studio in Cathedral Square with Leonard Booth and Sydney Thompson. Leonard Booth recounted to the writer that this studio was a very lively centre for painting in the city, and attracted many artists and visitors. In 1906 McIntyre returned to the art school and resumed his studies at a more advanced level.

Booth also recalled that McIntyre had a very attractive personality. He was regarded as 'Whistlerian' in temperament and 'lived his art'. Above all, he was scorned for being 'an adherent of Impressionism'. With such a reputation it is not difficult to imagine that he was somewhat estranged from Christchurch society in general and the recognised art circles in particular. Moreover, from early childhood he suffered from poor health and was inclined not to mix readily: but his friendships with writers and musicians would indicate a man who not only enjoyed other arts but possessed a fair knowledge of them also. He was, in addition, a fine 'cello player.

From the little we know it may be assumed that prior to 1909 Raymond McIntyre's knowledge and experience of art was limited to the teaching in the School of Art, and artists in Christchurch. In retrospect it seems as if this would be fairly restricted: but, in those days, Christchurch had a reasonable claim to be the major centre of artistic activity in the colony. While his own artistic activity in New Zealand was confined largely to painting, he did illustrate some of his own books: one on the actor W. Butler and another of thumbnail sketches of some characters he knew. These illustrations have traces of post-art-nouveau manner, coupled with elements of the style of the Beggarstaff Brothers4 in which attention is focused on the main design and detail is eliminated. In view of these illustrations and the paintings from this period his work reflects strongly the main stream of British art of a decade earlier. His tones are carefully modulated and the colours muted: often a delicately-organised series of greys. In looking at the English painting of the times {for instance William Nicholson) it is clear where his sources lay. English painting of that era had not yet been influenced by the more lively palettes of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

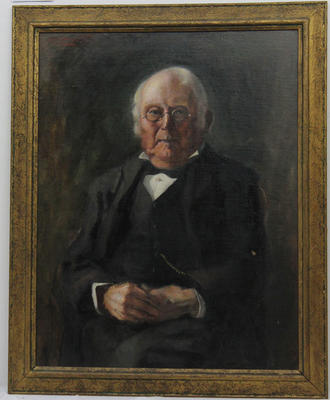

McIntyre's interest in portraiture was evident from an early age, and in the National Collection are several early works which exemplify his style and methods. Constance McIntyre, an oil painting of 1905, is small but well painted. She is dressed in a stylish manner, and the almost full profile pose enables McIntyre to accentuate the elegant line for which he is noted. The paint is applied loosely but the draughtmanship is very firm. The Woman in Furs (1906) is a marked development on the previous work and, difference in size apart, there is a more monumental and ordered approach to the subject. The tones are precise and the colours are modulations of a grey-brown with a hint of terre verte in the lighter sections. As with the Constance McIntyre the subject-matter is that of a well-dressed and elegant young woman: a subject he returns to in a Head of a Woman dated 1908. By now, his palette had lightened considerably and the overall tonality is greatly heightened. Again, McIntyre favours the profile portrait and the head floats above a light-coloured dress and against an equally light-toned background. It was apparent that at this stage of his career McIntyre had a very sensitive eye and was technically well-equipped. In retrospect it seems as if he felt he had done as much as he could in his native country and needed the stimulus of a more competitive art world to develop his talents.

Early in 1909 McIntyre decided to go to England to further his experience and to make his way as an artist in the much more exciting world of European art.5 Upon arrival he settled into London Bohemian life and rented a studio on Cheyne Walk ('next to Whistler's studio'). In the early days he received support from his father after he had been informed by him that one could live very well in London on 150 a year.6 Additional amounts were sent from time to time to supplement his modest way of life and these he gratefully acknowledged in his letters to his family.

In 1910 McIntyre began art studies at the Westminster Technical Institute under William Nicholson (one of the Beggarstaff brothers) and Walter Sickert. Nicholson he admired as 'one of the great British artists' but he found Sickert's methods too restrictive and his personal life unacceptable. His references to work he saw and admired give a hint of his personal tastes. He was drawn to the works of artists like Nicholson and Wilson Steer, and to Pre-Raphaelite painting in general. If anything, he was dismayed by the second exhibition of the Post-Impressionists whose work he saw in the Grafton Galleries, referring to some of them as 'horrors'. In the light of his later development of colour and composition it is remarkable that he was not more receptive to their work than his comments indicate. On the other hand it must be remembered that few artists and critics did accept this work, and only Roger Fry emerged as their great champion.

By 1911 one infers from some of McIntyre's letters that he was quite well- established and had made some useful and agreeable friends. One, Mrs Flora Lion, a London portrait and landscape painter of some note in the period prior to and immediately after World War I introduced the young colonial painter into the complex art world of London. Although shy and retiring he could be charming and kind and this was of importance in his attempts to promote his work: but it must be stressed that he did not indulge in any 'hard selling' methods. Indeed, his successes were achieved almost in spite of himself and he regarded worldly success with indifference. On reading his letters it is clear that his parents felt he should be striving harder for recognition.

On many occasions he was almost penniless and lived in poor conditions: but not once does he seem to have complained about his lot. He was philosophical by nature and was a Christian Scientist, accepting life as it presented itself day by day. Nevertheless, in spite of what might have appeared to his family as a remarkable lack of initiative and enterprise, he made ground slowly, and as early as 1912 he was selling a few works through Goupil & Co. This gave him the confidence to continue working.

McIntyre visited France, perhaps for the first time, in August 1912, and it was his stated intention to go to Normandy.11 He seems to have spent a few weeks at St. Malo without moving away from the city, and so far no works have been drawn to this writer's attention as being painted during that visit. From the time of the outbreak of World War I his movements become more difficult to reconstruct. Leonard Booth said he had heard that McIntyre spent some time as a lorry driver but substantiation for this has not been found. It is known that he found time to paint and exhibit during these years and this placed him in a convenient position for furthering his career once peace came. Prior to going to London McIntyre generally dated his work. After arriving in London, however, he usually omitted the date, which makes a chronological development difficult to establish. The Portrait of a Lady, exhibited in the N.E.A.C. in 1911 and the Goupil Gallery in 1912, is revealing because it still has the dark umbers and low tonality associated with his work produced in New Zealand. The paint is applied in a much more juicy fashion, with (for McIntyre) quite a heavy impasto. What is striking about this work is the more sensitive positioning of the figure, in profile, while the head is turned away from the viewer leaving a section of the neck and a small area of cheek to be seen, giving the impression that he was aware of work by Vuillard or a follower.

One work, Self Portrait (August 1915), enables one to see the development that has occurred over the six years he had been in London. The immediate impression gained is of the much more assured handling of the composition, which is very stylish and refined. The work, while loosely-handled, is nevertheless very precise and it is clear that the loose handling is due to his greater skill and confidence. The head is more worked on than the torso or the background - obviously a tantalising glimpse of the artist's studio. The work still relies on a series of carefully-orchestrated greys: but now he is extracting a resonance from the juxtaposition of complementary colours, seen in the head. The elegant linearity of the work is delightful and the lines of the body intersect with another curved line of a cane chair. This must rank as one of his major works and while he produced more highly-finished paintings none eclipse this in its achievement.

McIntyre continued to paint with great conviction and intensity after the war. In October 1918 he held a large exhibition at the Eldar Gallery; and in 1921, as a member of the Monarro Group, exhibited in the Goupil Gallery alongside Paul Signac, M.L. Pissarro and Lemaitre. He must have been regarded quite highly by Goupil's for them to have placed his work in an exhibition with such artists as these. In 1926 it is fairly certain that he visited France again. The painting Morning on the Seine would seem to be a Parisian view of that period. The work is restrained, and reflects Whistler's influence, both in colour (largely blue-greys) and composition - a bridge across a river and some apartments and trees on the far bank.

For some years McIntyre was art critic for the Architectural Review. In that capacity he appeared to be a sensitive critic - with occasional lapses. He did not, for instance, admire the exhibition of Cezanne's watercolours and drawings shown in the Leicester Galleries in 1925: he felt they were 'piffling'.12 But few critics were so confident of Cezanne's stature in the mid-twenties as to lavish praise on all his work. However, McIntyre's reviews praised the works of Heckel, Signac and Hodler.

Although McIntyre's reputation as an artist grew steadily from the early 1920s he did not receive great financial reward. The recollections of those who knew him in those years testify to the fact that he had little money for food, clothing or lodgings. Nevertheless, he was uncomplaining, and in physical appearance he was neat and tidy even though his clothes were often threadbare. He was an attentive host to those who called on him and he was careful to keep his friendships alive and visit his acquaintances regularly. His health, always fragile, deteriorated suddenly and he died of a strangulated hernia on 24 September 1933. It could have been operated on but, faithful to his Christian Science beliefs, he refused to have the treatment and operation which surely would have saved him.13 From a conventional viewpoint his death was unnecessary: but from McIntyre's own viewpoint he lived his life honestly and fully according to his philosophy. So at what now seems an early age of fifty-four his promising career was cut off.

In retrospect his art was of a very high standard. It reflected contemporary British trends and, perhaps most of all, the influence of French art of the turn-of- the-century, especially that of Vuillard and the Nabis in general.14 Once he left New Zealand he left behind the dull earth-colours - the umbers, the ochres - and moved into a series of harmonically-subtle greys which at times had a pearl-like translucency. There is little doubt that Raymond McIntyre was a gifted artist of great sensitivity who needed to leave his native land to mature in the much more sympathetic milieu of a large city. One great regret, finally, is that a zealous housekeeper 'cleaned up' his studio immediately after his death and destroyed correspondence, sketches and studies - all of which might have led us to a better understanding of a remarkable man.

(http://www.art-newzealand.com/Issues1to40/mcintyre.htm)

Of the many New Zealand painters who left their native country to work overseas none has proved so elusive as Raymond McIntyre. The difficulties one experiences in coming to grips with the man and his work are due to the fact that he was a self-effacing and very private person, who took great pains to conceal his feelings from most of his family and friends. The resultant lack of knowledge has been frustrating, because the last few years have seen a growing interest in his work. Not only is the quality of his painting superb: more than that, it shows an acute awareness of contemporary trends in European art of the early twentieth century.

Born in Christchurch, McIntyre was one of seven children of George McIntyre, a one-time mayor of New Brighton. His formal education finished when he was fifteen years of age, and he began art studies at the Canterbury School of Art, where he was taught by Herdman Smith and Alfred Walsh.1 A break in his training occurred between 1901 and 1906, during which time he shared a studio in Cathedral Square with Leonard Booth and Sydney Thompson. Leonard Booth recounted to the writer that this studio was a very lively centre for painting in the city, and attracted many artists and visitors. In 1906 McIntyre returned to the art school and resumed his studies at a more advanced level.

Booth also recalled that McIntyre had a very attractive personality. He was regarded as 'Whistlerian' in temperament and 'lived his art'. Above all, he was scorned for being 'an adherent of Impressionism'. With such a reputation it is not difficult to imagine that he was somewhat estranged from Christchurch society in general and the recognised art circles in particular. Moreover, from early childhood he suffered from poor health and was inclined not to mix readily: but his friendships with writers and musicians would indicate a man who not only enjoyed other arts but possessed a fair knowledge of them also. He was, in addition, a fine 'cello player.

From the little we know it may be assumed that prior to 1909 Raymond McIntyre's knowledge and experience of art was limited to the teaching in the School of Art, and artists in Christchurch. In retrospect it seems as if this would be fairly restricted: but, in those days, Christchurch had a reasonable claim to be the major centre of artistic activity in the colony. While his own artistic activity in New Zealand was confined largely to painting, he did illustrate some of his own books: one on the actor W. Butler and another of thumbnail sketches of some characters he knew. These illustrations have traces of post-art-nouveau manner, coupled with elements of the style of the Beggarstaff Brothers4 in which attention is focused on the main design and detail is eliminated. In view of these illustrations and the paintings from this period his work reflects strongly the main stream of British art of a decade earlier. His tones are carefully modulated and the colours muted: often a delicately-organised series of greys. In looking at the English painting of the times {for instance William Nicholson) it is clear where his sources lay. English painting of that era had not yet been influenced by the more lively palettes of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

McIntyre's interest in portraiture was evident from an early age, and in the National Collection are several early works which exemplify his style and methods. Constance McIntyre, an oil painting of 1905, is small but well painted. She is dressed in a stylish manner, and the almost full profile pose enables McIntyre to accentuate the elegant line for which he is noted. The paint is applied loosely but the draughtmanship is very firm. The Woman in Furs (1906) is a marked development on the previous work and, difference in size apart, there is a more monumental and ordered approach to the subject. The tones are precise and the colours are modulations of a grey-brown with a hint of terre verte in the lighter sections. As with the Constance McIntyre the subject-matter is that of a well-dressed and elegant young woman: a subject he returns to in a Head of a Woman dated 1908. By now, his palette had lightened considerably and the overall tonality is greatly heightened. Again, McIntyre favours the profile portrait and the head floats above a light-coloured dress and against an equally light-toned background. It was apparent that at this stage of his career McIntyre had a very sensitive eye and was technically well-equipped. In retrospect it seems as if he felt he had done as much as he could in his native country and needed the stimulus of a more competitive art world to develop his talents.

Early in 1909 McIntyre decided to go to England to further his experience and to make his way as an artist in the much more exciting world of European art.5 Upon arrival he settled into London Bohemian life and rented a studio on Cheyne Walk ('next to Whistler's studio'). In the early days he received support from his father after he had been informed by him that one could live very well in London on 150 a year.6 Additional amounts were sent from time to time to supplement his modest way of life and these he gratefully acknowledged in his letters to his family.

In 1910 McIntyre began art studies at the Westminster Technical Institute under William Nicholson (one of the Beggarstaff brothers) and Walter Sickert. Nicholson he admired as 'one of the great British artists' but he found Sickert's methods too restrictive and his personal life unacceptable. His references to work he saw and admired give a hint of his personal tastes. He was drawn to the works of artists like Nicholson and Wilson Steer, and to Pre-Raphaelite painting in general. If anything, he was dismayed by the second exhibition of the Post-Impressionists whose work he saw in the Grafton Galleries, referring to some of them as 'horrors'. In the light of his later development of colour and composition it is remarkable that he was not more receptive to their work than his comments indicate. On the other hand it must be remembered that few artists and critics did accept this work, and only Roger Fry emerged as their great champion.

By 1911 one infers from some of McIntyre's letters that he was quite well- established and had made some useful and agreeable friends. One, Mrs Flora Lion, a London portrait and landscape painter of some note in the period prior to and immediately after World War I introduced the young colonial painter into the complex art world of London. Although shy and retiring he could be charming and kind and this was of importance in his attempts to promote his work: but it must be stressed that he did not indulge in any 'hard selling' methods. Indeed, his successes were achieved almost in spite of himself and he regarded worldly success with indifference. On reading his letters it is clear that his parents felt he should be striving harder for recognition.

On many occasions he was almost penniless and lived in poor conditions: but not once does he seem to have complained about his lot. He was philosophical by nature and was a Christian Scientist, accepting life as it presented itself day by day. Nevertheless, in spite of what might have appeared to his family as a remarkable lack of initiative and enterprise, he made ground slowly, and as early as 1912 he was selling a few works through Goupil & Co. This gave him the confidence to continue working.

McIntyre visited France, perhaps for the first time, in August 1912, and it was his stated intention to go to Normandy.11 He seems to have spent a few weeks at St. Malo without moving away from the city, and so far no works have been drawn to this writer's attention as being painted during that visit. From the time of the outbreak of World War I his movements become more difficult to reconstruct. Leonard Booth said he had heard that McIntyre spent some time as a lorry driver but substantiation for this has not been found. It is known that he found time to paint and exhibit during these years and this placed him in a convenient position for furthering his career once peace came. Prior to going to London McIntyre generally dated his work. After arriving in London, however, he usually omitted the date, which makes a chronological development difficult to establish. The Portrait of a Lady, exhibited in the N.E.A.C. in 1911 and the Goupil Gallery in 1912, is revealing because it still has the dark umbers and low tonality associated with his work produced in New Zealand. The paint is applied in a much more juicy fashion, with (for McIntyre) quite a heavy impasto. What is striking about this work is the more sensitive positioning of the figure, in profile, while the head is turned away from the viewer leaving a section of the neck and a small area of cheek to be seen, giving the impression that he was aware of work by Vuillard or a follower.

One work, Self Portrait (August 1915), enables one to see the development that has occurred over the six years he had been in London. The immediate impression gained is of the much more assured handling of the composition, which is very stylish and refined. The work, while loosely-handled, is nevertheless very precise and it is clear that the loose handling is due to his greater skill and confidence. The head is more worked on than the torso or the background - obviously a tantalising glimpse of the artist's studio. The work still relies on a series of carefully-orchestrated greys: but now he is extracting a resonance from the juxtaposition of complementary colours, seen in the head. The elegant linearity of the work is delightful and the lines of the body intersect with another curved line of a cane chair. This must rank as one of his major works and while he produced more highly-finished paintings none eclipse this in its achievement.

McIntyre continued to paint with great conviction and intensity after the war. In October 1918 he held a large exhibition at the Eldar Gallery; and in 1921, as a member of the Monarro Group, exhibited in the Goupil Gallery alongside Paul Signac, M.L. Pissarro and Lemaitre. He must have been regarded quite highly by Goupil's for them to have placed his work in an exhibition with such artists as these. In 1926 it is fairly certain that he visited France again. The painting Morning on the Seine would seem to be a Parisian view of that period. The work is restrained, and reflects Whistler's influence, both in colour (largely blue-greys) and composition - a bridge across a river and some apartments and trees on the far bank.

For some years McIntyre was art critic for the Architectural Review. In that capacity he appeared to be a sensitive critic - with occasional lapses. He did not, for instance, admire the exhibition of Cezanne's watercolours and drawings shown in the Leicester Galleries in 1925: he felt they were 'piffling'.12 But few critics were so confident of Cezanne's stature in the mid-twenties as to lavish praise on all his work. However, McIntyre's reviews praised the works of Heckel, Signac and Hodler.

Although McIntyre's reputation as an artist grew steadily from the early 1920s he did not receive great financial reward. The recollections of those who knew him in those years testify to the fact that he had little money for food, clothing or lodgings. Nevertheless, he was uncomplaining, and in physical appearance he was neat and tidy even though his clothes were often threadbare. He was an attentive host to those who called on him and he was careful to keep his friendships alive and visit his acquaintances regularly. His health, always fragile, deteriorated suddenly and he died of a strangulated hernia on 24 September 1933. It could have been operated on but, faithful to his Christian Science beliefs, he refused to have the treatment and operation which surely would have saved him.13 From a conventional viewpoint his death was unnecessary: but from McIntyre's own viewpoint he lived his life honestly and fully according to his philosophy. So at what now seems an early age of fifty-four his promising career was cut off.

In retrospect his art was of a very high standard. It reflected contemporary British trends and, perhaps most of all, the influence of French art of the turn-of- the-century, especially that of Vuillard and the Nabis in general.14 Once he left New Zealand he left behind the dull earth-colours - the umbers, the ochres - and moved into a series of harmonically-subtle greys which at times had a pearl-like translucency. There is little doubt that Raymond McIntyre was a gifted artist of great sensitivity who needed to leave his native land to mature in the much more sympathetic milieu of a large city. One great regret, finally, is that a zealous housekeeper 'cleaned up' his studio immediately after his death and destroyed correspondence, sketches and studies - all of which might have led us to a better understanding of a remarkable man.

(http://www.art-newzealand.com/Issues1to40/mcintyre.htm)